Chapter 4: The Sports Science Behind NASCAR

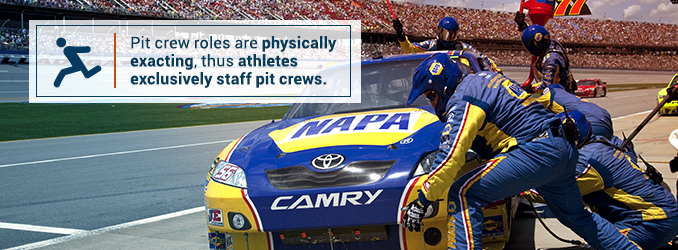

Pit crew members are subject to some very exacting standards. When 6,000 researchers met for the American College of Sports Medicine’s (ACSM) 61st Annual Conference in late May of 2014, the reasons why became clear.

The meeting’s third installment of sports science took the conversation in the direction of racing and went on to explain how athletes exclusively staffed pit crews. Every position on the six-man team is reserved for a star performer.

For crew chiefs, this means hiring top college-level talent and finding those candidates who can successfully substitute the playing field for NASCAR’s infield.

Pit Crew Selection Criteria

Like in many other sports, an individual’s physical dimensions and athletic ability affect their potential standing within a team. Where NASCAR is concerned, these attributes go a long way towards determining who is assigned what role.

According to Dr. J. Timothy Lightfoot, director at the Huffines Institute in Texas and speaker at the ACSM Conference, pit crew recruiting strategies have been based around such principles since the early 1990s, when teams realized they could shave precious seconds off the clock.

Today’s decisions are made with reference to:

- Body composition, muscle mass and fat distribution

- Endurance, and particularly forearm strength

While these attributes may seem to have little impact on the surface at first glance, in actuality, they impact the selection process in a major way.

Physical Attributes

Each of the six positions available in the modern formation of the pit crew are generally suited to a specific type of person with a specific set of characteristics. While there will be the occasional athlete who defies all attempts at categorization, most candidates will be selected for their ability to fit the mold.

For example, any jackman must be in possession of considerable strength if he is to raise the 3,500-pound car with as little effort as possible. Similarly, the front and rear tire changers, working as low as they do, are better off if they are shorter than average and have a slightly lower center of gravity.

Athleticism

Evaluating a person’s athleticism may seem arbitrary in light of the fact that the fastest pit crews are done with their work inside of 12 seconds, but the reality is that every fraction of a second counts.

Physical ability, while desirable, is not the only factor crew chiefs evaluate. Mental acuity is often tested to the extreme because pit crew members must remain aware of their surroundings and execute forward thinking in the face of quickly changing circumstances. After all, pit road can be a dangerous place.

One of the first teams to combine the athlete’s mindset with the job at hand was Hendrick Motorsports, winner of 11 car owner championships in NASCAR’s Sprint Cup series.

The team, led by Rick Hendrick, saw an untapped opportunity in the college football teams of the 1990s and began scouting potential specialists. This strategy is widely credited with triggering a change in the way pit crews would be formed across the sport.

Today’s candidates who satisfy most — if not all — of the selection criteria are then allowed to progress and go on to learn the practical aspects of the job.

Training and Maneuvers

Many of the maneuvers employed by pit crews during a race are incredibly minute, and have to do with small, time-efficient movements. Tire changers are arguably the most important member of the pit crew. Their role is one that invites the possibility of human error at every turn.

In fact, tire changers are trained to remove all five lug nuts from each wheel in one to 1.2 seconds and not a millisecond faster. At speeds of nine tenths of a second for example, the embedded sense of metronomic memory that is developed is interrupted and this can cause the crewman to make more mistakes.

But what is the true measure of a mistake? And how do they impact people’s careers when every member of the team is under constant scrutiny from crew and car chiefs, the media and officials? Well, the flow-on effects can be varied, and devastating.

Impact of Imprecision

Missing a lug nut by as little as one millimeter can add an extra three tenths of a second to the clock and cost the racer around 90 feet or five car lengths. As the average margin of victory is around 1.7 seconds for modern circuits, getting it right the first time is a must.

Those who are unable to operate at their peak and with a high degree of consistency will be viewed as a liability before long. Fortunately, training regimes are designed to ready potential pit road members for worst case race-day scenarios and have a tendency to produce the best of the best.

Table of Contents

- The Tools of a NASCAR Pit Crew

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: A Brief History of Pit Crew Racing

- Chapter 2: Structure of Race Car Pit Crews

- Chapter 3: Anatomy of the 12-Second Pit Stop

- Chapter 4: The Sports Science Behind NASCAR

- Chapter 5: Evolution of Tools and Racing Equipment

- Chapter 6: Factors Affecting Podium Positions

- Chapter 7: The Future of Pit Crews

- Conclusion: NASCAR as a National Phenomenon